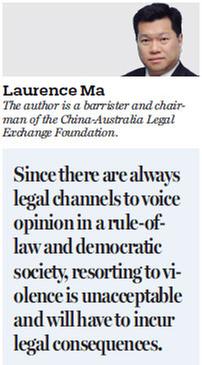

New sentences on trio legally well-grounded

Lawrence Ma points out presence of violence at the protest - key issue in sentence revision - carries strong precedents

On Aug 17, Hong Kong's Court of Appeal sentenced student activists Joshua Wong Chi-fung, Nathan Law Kwun-chung and Alex Chow Yong-kang to between six and eight months in prison for their leading roles in the storming by a few hundred student protesters of the government headquarters' square in 2014, which set off the 79-day illegal "Occupy Central" movement.

During the storming of the headquarters, protesters inflicted damage with metal barricades, broke police cordons and injured 10 security guards and disregarded police warnings twice before charging into the government premises.

The sentence was a revised one. The three were originally given much lighter punishments by an eastern court magistrate - some 80 hours community service orders or a suspended short jail term.

The lenient punishment stirred huge outcry in society. Many were confused by the mismatch between the damage brought to society and the punishment received. Thus after the Department of Justice filed an application for sentencing review, the Court of Appeal reversed the magistrate's sentences as the judges found a number of evident errors.

Firstly, the magistrate did not consider the deterrent effect of her sentences.

The correct legal principle, accepted and applied in the English Court of Appeal in R v Asim Alhaddad (2010) EWCA Crim 1760 was that sentence for unlawful assembly coupled with violence mandated a term of imprisonment. Those are serious crimes. A community service order was not appropriate for serious crimes and unlawful assembly with violence which caused actual injury.

For serious crimes, the deterrent effect had to be given significant weight and consideration; failing to do so rendered the sentence manifestly inadequate.

Secondly, the magistrate erred in judging that their actions did not involve any serious violence. She failed to take into account the fact that it was a large-scale unlawful assembly where there was a high risk of physical confrontation that could result in injury. And in fact, injury to others did occur.

Wong and his allies must have foreseen the possibility of physical confrontation among the protesters, police and security guards.

It is a long-established precedent that freedom of protest is honored as a general right but the protest must be free from any violence. From the well-recognized judgment of Sachs LJ in the English Court of Appeal R v Caird (1970) 54 Cr App R 499 that: "when there is wanton and vicious violence of gross degree the Court is not concerned with whether it originates from gang rivalry or from political motives.

"It is the degree of mob violence that matters and the extent to which the public peace is being broken" and that "the law has always leant heavily against those who, to attain such a (political) purpose, use the threat that lies in the power of numbers."

Since there are always legal channels to voice opinion in a rule-of-law and democratic society, resorting to violence is unacceptable and will have to incur legal consequences. Regardless of whether the protesters had good and righteous intentions, or where the "circumstances so compelled", or others might be more culpable, all in all these would not be grounds for mitigation according to legal principles and past case rulings.

Thirdly, the magistrate ignored the fact that the forcible entry was a blatant disregard of the law because Wong and his allies had distributed leaflets advising protesters on how to obtain help after being arrested.

Lastly, the magistrate mistakenly regarded that Wong and his allies showed repentance toward their wrongdoings.

The fact that they said they would "respect the court and were willing to shoulder responsibility of their actions" was in fact not a statement of remorse or contrition. The Court of Appeal regarded that showing respect to the court was a matter of course. The trio maintained that "civil disobedience" was still the right path to take without fear. This was evidence of no repentance.

The reversed sentence showed that Hong Kong's judicial system is capable of correcting its own mistakes via appeals and re-examination of facts. The system also offers an environment for the judges to be impartial and independent. If one has read the ruling, he or she will discover that decision is made in accordance with laws and in no point politically motivated. The judiciary knew that it shoulders the responsibility to uphold the rule of law and to draw a proper legal balance between public order and people's right to protest.

However, unfortunately, the judges faced insult from the trio's supporters as they think the ruling is "political persecution". Some even called them "unscrupulous judges" on social media platforms.

Reasoned, constructive criticisms are always welcome but unfounded, biased accusations are prohibited. Slandering and scandalizing judges or posting threats of whatever form is a contempt of court, an offense that may result in a maximum two years' imprisonment. Contempt of court is not limited to actions and statements made inside the precinct of the court but also outside.

(HK Edition 09/01/2017 page11)

Today's Top News

- Xi's article on public, non-public sectors to be published

- LAMOST data helps solve century-old cosmic puzzle

- AI labeling to fight spread of fake info

- Confidence expressed in growth outlook

- New tool helps predict recurring liver cancer

- China, Russia, Iran call for more dialogue