Bringing best brains to rural schools

An NGO is helping to overcome a shortage of skilled teachers in some of China's most isolated areas

In the past decade, a nonprofit organization has been trying to reverse an imbalance in the quality of education provided in urban and rural areas. Since 2008, Teach for China has been sending graduate volunteers from some of the country's top universities to teach in remote villages and address a shortage of talented teachers. The program is now beginning to reap real rewards.

When He Liu arrived at the middle school in Dazhai village, Yunnan province, seven years ago, the local children had never heard of Beethoven, Chopin or other composers, and they often looked confused when their new teacher played a nocturne in class or showed them DVDs of The Phantom of the Opera. For the students, anything from outside their isolated village was entirely unknown, and therefore hard to comprehend.

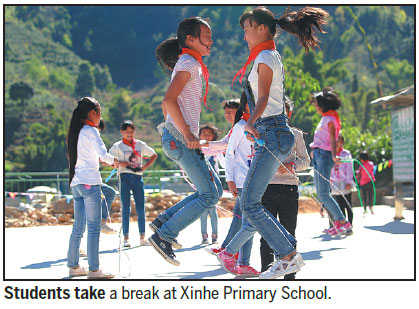

| Chen Chen, a Teach for China volunteer, teaches an English class at Xinhe Primary School in Dazhai village, Yunnan province. Photos Provided to China Daily |

"But as they listened to more songs and watched more movies, I saw signs that they were enjoying themselves. Some would nod their heads to the music and pretend they were conducting," says the 29-year-old graduate of Beijing Normal University, recalling the change in his former students.

After graduating in 2010, He traveled to the mountainous region to work as a history teacher. He discovered that most of the teachers in the village had graduated from vocational schools and could teach little more than the contents of textbooks.

"In addition, the parents, who had been farmers all their lives, or worked in big cities and left their children in the care of their grandparents, could only provide limited knowledge. Those factors were taking a toll on the students," he says.

Feng Qingli, who was head teacher during He's time in the village, says its isolated location hampers the children's progress. "Nearly all of them work hard, but the problem is that they have limited contact with the outside world, so their vision is narrow," he says.

Zhang Yue, one of He's former students, followed in her old teacher's footsteps and studied in Beijing, attending Beihang University. She says He helped to broaden her horizons and was a lasting influence on her life.

"When I was young, the village seemed to be the entire world to me. It was Mr He who made me realize that our village is so small and that I could go out and see the world if I worked hard," she says.

According to Teach for China, about 1,000 fresh graduates from China's top universities joined its program between 2008 and 2016. In 2006, about 470 classes involved with the program nationwide saw average marks rise, and more than 420 registered a surge in the number of students who regularly scored more than 80 percent in exams.

Since the reform and opening-up policy started in the late 1970s, China's economy has grown to become the second-largest in the world. However, the downside is that the country's rapid rate of urbanization has widened the urban-rural divide, and the gulf in the education sector is one of the most worrisome problems, according to experts.

Wang Liwei, a researcher at the 21st Century Education Research Institute, a nonprofit organization in Beijing that focuses on education policy research and advocacy, says the quality of rural education is significant because a high proportion of the population still lives in the countryside.

"Poor education in isolated areas compromises the quality of the rural workforce, and that could hamper the country's development. People whose low educational status makes them unemployable also pose a threat to social stability," she says.

In the past decade, the government has spent ever-increasing sums on upgrading the infrastructure of rural schools, providing better buildings and facilities and introducing preferential policies to attract skilled teachers to isolated areas.

In 2007, the State Council, China's Cabinet, implemented the Free Normal Education Program in six "normal" universities, which are colleges that train teachers for all levels.

Students admitted to the program are exempt from tuition fees and also receive a monthly allowance of 600 yuan ($90; 76 euros; £68) while on campus. Following graduation, they spend a specified period teaching in regions where teachers are in short supply.

In 2010, the National Training Program for Primary and Secondary School Teachers was implemented jointly by the ministries of education and finance. Under the program, village teachers in central and western China were given the opportunity to take free refresher courses or attend short-term training sessions at top universities at the State's expense.

In 2012, central government spending on education reached 2.7 trillion yuan, surpassing 4 percent of national GDP for the first time, according to the Ministry of Education. The figure has been rising ever since, and last year it hit 3.8 trillion yuan, accounting for 5.2 percent of GDP.

The increased investment means rural students no longer have to worry about crumbling school buildings, while internet access and multimedia teaching facilities are now commonplace.

"If you take a tour of the countryside now, it's amazing to see that schools are always the fanciest buildings," says Andrea Pasinetti, founder and CEO of Teach for China.

However, according to Wang, the researcher, despite the improved infrastructure, some rural areas are still experiencing severe shortages of skilled teachers.

"The lack of talented teachers means the better-off parents send their children to schools in nearby townships and big cities but, in return, the loss of students exacerbates the problem of teacher shortages because they also gravitate toward larger towns. It's a vicious circle."

Pasinetti, a US-Italian dual national, founded Teach for China in 2008, basing the organization on the model of Teach for America. Its Chinese name is Meili Zhongguo, meaning "Beautiful China".

Unlike other education assistance programs, Teach for China does not advocate a one-way street, whereby teachers become permanent fixtures in isolated spots. Instead, it emphasizes the mutual benefits the two-year program offers teachers and students alike.

Liu Pengze, director of the Beijing Lead Future Foundation, an NGO that provides most of the funding for Teach for China, says volunteer teaching programs are not a new phenomenon in China, which has seen the Hope Project and other initiatives, but nearly all of them advocate a lifelong devotion to teaching at the grassroots level.

"The unequal access to quality education is a result of urbanization, so therefore it's unfair to expect these young talents to travel to unappealing, isolated villages and teach in them for the rest of their lives," he says.

Before they enter the classroom, each graduate in the Teach for China program undertakes a training course that lasts four to six weeks. The course provides introductions to teaching methods, management skills and local customs, and helps the students to hone their skills through multiple trial lectures. During training they are given a monthly stipend of 2,200 yuan, but once they are in the field, they receive 2,800 yuan a month.

According to Pasinetti, although the financial rewards are low, the graduates benefit greatly from the experience.

"Few employers would leave demanding tasks to new employees and let them assume huge responsibility, but in rural primary schools, our graduates are like the CEOs of each class," he says.

He Liu, the teacher, says his experience in Dazhai helped to formulate a pattern of thinking that he has retained. "The teaching process is objective-oriented and requires a clear plan. It molded my thought pattern, which I apply to my everyday tasks."

Statistics supplied by Teach for China show that the graduates become more willing to stay in the education sector as they progress through the two-year program. "Initially, only about 6 or 7 percent say they will stay in education after their placement, but the number rises to 70 percent when they finish the program," Liu says.

According to the NGO, more than 50 percent of its graduate volunteers either stay in the sector after finishing their teaching stints, or they join nonprofit organizations similar to Teach for China.

Now, the Beijing Lead Future Foundation is pushing forward another program called Meili Xiaoxue, or "Beautiful Primary School", to offer opportunities to previous graduate volunteers who want to contribute further.

The schools enlisted in the Meili Xiaoxue program remain under the administration of the local education authorities, but they hand over their management to the foundation and teaching duties to Teach for China.

"Now we have two such schools in place and they are just like two laboratories. What we want to do is to explore a new approach for rural education, which can be copied in other parts of China," Pasinetti says.

lilei@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 11/24/2017 page19)

Today's Top News

- DPP authorities will be held accountable for each and every secessionist move

- Ministry to expand carbon trading program

- A new global economic order, if it can be built

- China further opens its door to attract FDI

- European officials' visits set to bolster trust

- 4.2-magnitude quake strikes Hebei: CENC