Artful bliss in the garden of blankness

"I remember him saying: 'At last, a space big enough to hold my collection,'" Hearn says.

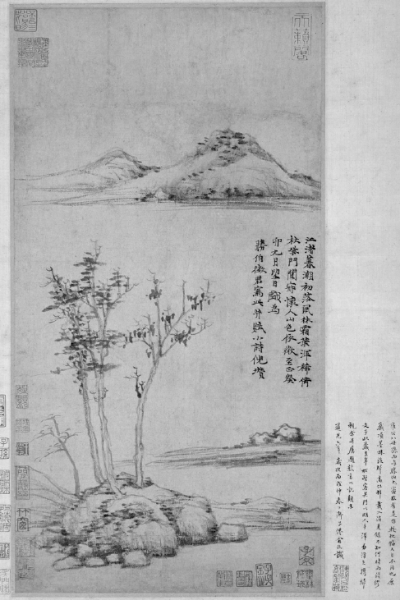

In the intervening years Hearn also learned Chinese, both modern and classical. However, the raw experience of looking at a powerfully executed piece of ancient Chinese calligraphy, of feeling the strength of every stroke while uncertain of the character's meaning, has stayed with him.

He tapped into that feeling as a curator, first with a 1972 show that juxtaposed calligraphic works from China with those from the Islamic and Western worlds, and then with an uncompromisingly contemporary one titled Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China, in 2014.

"Wen Fong was a great tennis player. He talked about calligraphy the same way you might talk about an athletic performance by Roger Federer. In both cases, it's about being in the moment while relying on the muscle memory of countless hours of practice - a combination of physical training, mental focus and spontaneity," he says, trying to explain the sense of thrill someone who is not Chinese might feel looking at a work of Chinese calligraphy.

"A skier navigating a course down a mountain slope might feel the same kind of excitement a calligrapher experiences with his brush," Hearn says.

"Westerners who know about action painting, about gesture and speed, about figure-ground relationship, about positive and negative spaces can understand calligraphy, for all the elements are there," he says, linking the millennia-old art tradition with influential abstract expressionists such as Jackson Pollock and Brice Marden.