Beijing - Preserving the city's cultural and historic heritage

Beijing—a city that would evolve from being a mere fascination to a deep passion—captivated me. Yet, when I first visited in 1987 as a traveler, I realized how little I knew of the city, despite my academic background in historical geography.

Thirty-eight years ago, visitors were introduced to grand historic legacies, such as the Forbidden City. However, I felt that little attention was given to the everyday living areas. At that time, I also felt that Beijing, compared to Western cities, was not as developed—something I came to understand better in later years.

In 1994, I began regularly staying in an older hutong near the Lama Temple (Yonghegong). The area was home to locals leading seemingly traditional lifestyles. It was truly fascinating to wander around, watch, and photograph the vibrant scenes unfolding daily. This was one of many reasons I kept returning to Beijing, eventually living there for many years.

Through walking the streets, I gradually began to appreciate the city's uniqueness, while also encountering cultural differences in how heritage was regarded and preserved.

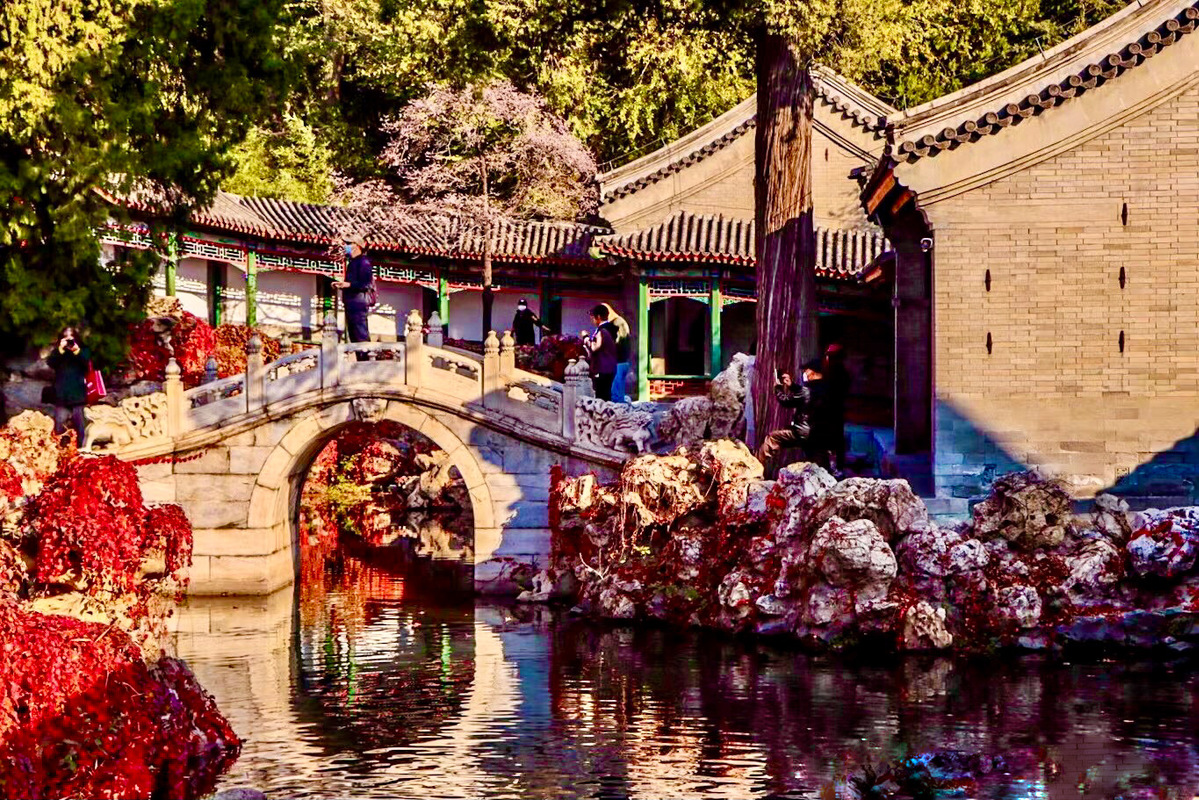

As a long time capital city, Beijing carries remnants of its historical dynasties, including Yuan, Ming and Qing. None grander than the spectacular Ming imperial palaces and temples, which have long attracted both domestic and international visitors. Additionally, some of the city's parks echo its royal past, originally designed as palatial gardens or hunting grounds.

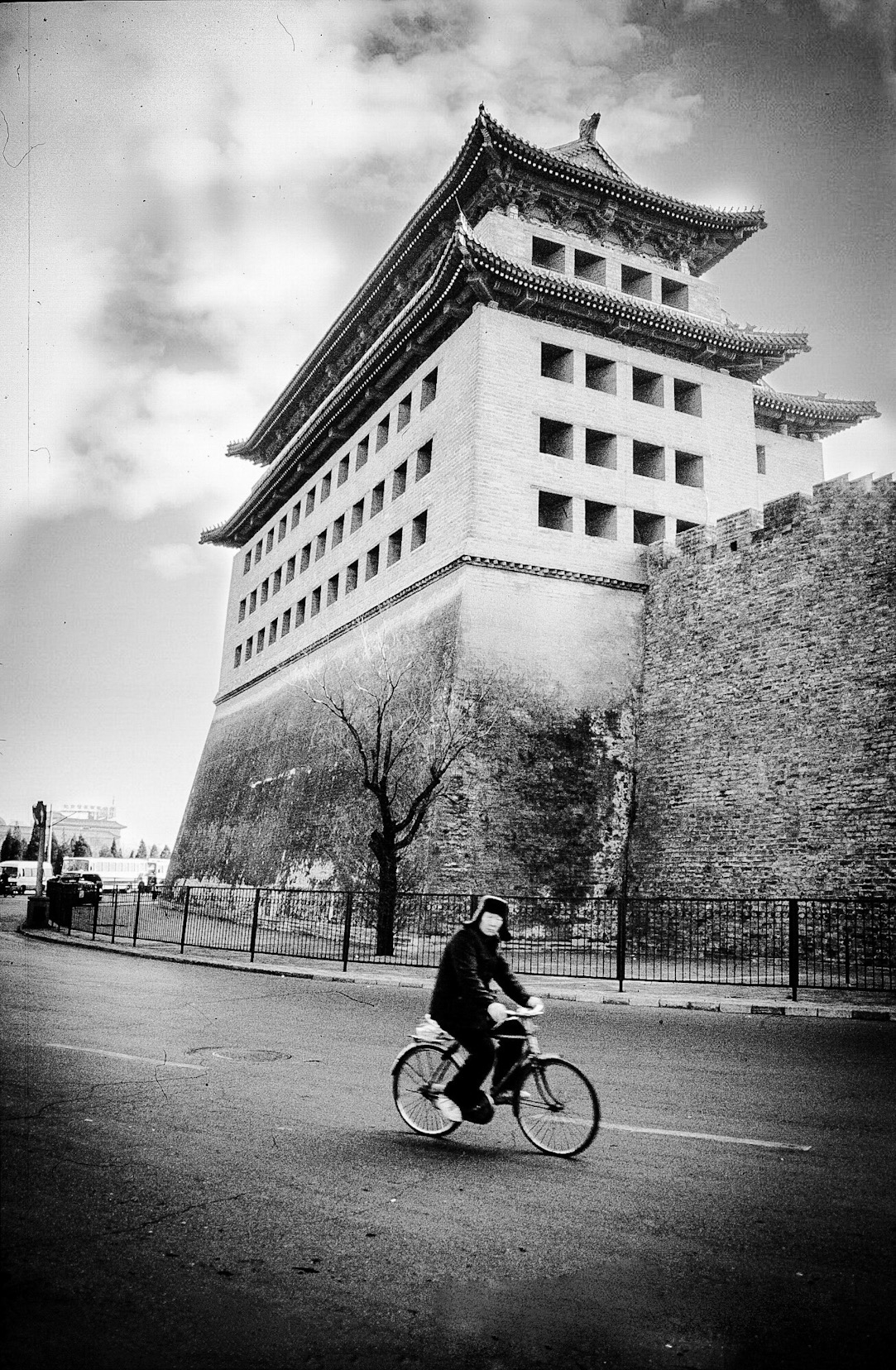

I carefully studied the remaining sections of the city walls from the Yuan and Ming eras. Massive gate towers, such as Deshengmen and Zhengyangmen, served as reminders of the city's defence, built to protect both the city and the emperors residing within its walls. I often followed the many canals and wandered around lakes, discovering that many were manmade as part of water management projects, some even linked to the Grand Canal for transportation. As a geographer, I became increasingly fascinated by Beijing's early layout, centered around its unique axis line—a significant factor in its role as the national capital. In the older hutong alleys within the historic inner city, my curiousity grew about their history and their future as the city embarked on its transformation into the modern era.

By the mid to late 1990s, I began to understand how local perceptions of these older areas differed from mine. Gaining insight into the country's long and complex history became essential for appreciating the depth of the city's evolution.

China was emerging from a century marked by conflict and destruction, with a society still struggling economically, particularly in comparison to Western nations. The primary focus during this period was development, aimed at creating a modern, prosperous society for its people. In fact, many were perplexed, and some even embarrassed by my fascination with what they considered the 'old'. There was a prevailing belief that to move forward, the old had to be replaced with the new—modern cities offering better lifestyles had to emerge from the remnants of the past. For example, many parts of Beijing had never changed or upgraded for a very long time. That was one of the many reasons I found the city so fascinating, as some areas felt like they were in a "time warp".

Another concept was the location often of greater significance than actual infrastructure. Most had not been constructed with a view towards longevity, instead rebuilding would happen on the same place even retaining original names. Often they were initially built of wood or simple materials, prone to fire, earthquake destruction or simply deteriorating with age. It would be fascinating whether they were actually original structures? For example, some of Beijing's earliest hutong alleys, dating from the 13th century Yuan Dynasty, were around the Bell and Drum Towers (Zhonggulou). Orientation of the alleys were from that period had been rebuilt several times.

Districts, such as today's Liulichang Culture Street, prospered during the Qing Dynasty, gaining fame for books, writing brushes, calligraphy and more. The area's name, translating literally as 'Colored Glaze Factory Street', originated from its importance during the Yuan and Ming Dynasties. The street, rebuilt in 1980, housed many of Beijing's famed 'Time Honored Brands' particularly centered on cultural heritage. I was first introduced to the area in 1994, not realizing it had been rebuilt, such was the quality of its restoration.

Gradually, as China became more prosperous, there was growing attention towards its heritage and historic legacy. Incredible, when I look back now to my first experience walking through Beijing's Forbidden City. I felt then it needed careful restoration to bring back its former glory. This indeed has happened, particularly with a sixteen year project commencing in 2005 to restore it to its pre-1912 state. Today, the work completed, it is a superb example of restoration. I have witnessed this progress across the city, with some splendid examples being Beihai Park; Summer Palace; the Fragrant Hill Park on the edge Beijing's Western Hills. Today, those are beautiful locations which I appreciate both for walking and photography.

Historically, Beijing was a city of walls within walls, with strong gates controlling both entry into and within the city where walls and gates separated local districts. However, during the Qing Dynasty's latter days, the walls had deteriorated through lack of maintenance and military activities, particularly in the early 20th century. Sadly in a ruined state, much was removed to make way for the city's development, such as Beijing subway's Loop Line. One example was the Inner City Wall, dating from 1419 during the Ming Dynasty. However, in the late 1990's, reconstruction started on a section running from massive southeastern corner Dongbianmen Tower towards Chongwenmen. Today a park runs alongside the wall. Another section directly north of Dongbianmen was also restored, indeed creating reminders of the early city's historic grandeur.

Other sections of city walls included a small section of the former Imperial City Wall at East Huangchenggen North Street. It now forms part of a lengthy, but delightful, linear park running down almost to Chang'an Avenue. It includes excavations of Ming-era relics east of the Forbidden City's Donghuamen Gate.

Predating the Ming Dynasty, the early 13th century Yuan Dadu ('Great Capital') was also walled. A lengthy northern section, known as Tucheng ('Earth Wall') was created as a park in 1988. Undergoing extensive restoration in 2003, it today offers an attractive 8.5 kilometer walk from Shaoyaoju westwards almost to Xizhimen.

Historically, dating from the Yuan Dynasty, Beijing was laid out in relation to a north-south Central Axis Line (zongzhouxian). Acting as a meridian, much of the early city was laid out along it in symmetry. Initially 3.7 kilometers long, it was eventually extended to 7.8 kilometers, running from the Bell and Drum Tower (Zhonggulou) south to Yongdingmen Gate. That gate, dating originally from 1553, was removed during the 1950's making way for construction of No 2 Ring Road. However, in 2005, it was reconstructed, standing now as a southern entrance into what was Beijing's historic core. In July 2024, the Central Axis was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. A section including Qianmen Pedestrian Street, was restored in 2008 from a formerly busy road. Today a popular tourist area, it runs directly south from historic, iconic, Jianlou Tower.

Although Beijing sits within a relatively dry area, of low rainfall, the city is home to an extensive network of canals along with a system of interconnected lakes. Mostly manmade, this had formed important elements for the city's early water supply and transportation system. They provided connectivity reaching from an extension of the Grand Canal almost to the Western Hills. In recent years, considerable work has been undertaken to clean the waters. This has resulted in excellent environmental areas for recreation including cycling, walking and even boating. They also provide traffic-free corridors from the central city up to the Summer Palace. Lake areas such as Shichahai, north of the Forbidden City, have undergone considerable transformation, attracting many visitors. Quite a contrast from my early days of exploring what were then regarded as 'backwaters'.

Beijing's hutong alleys have been a fasciation for me since 1994. However I recognised there were many problems such as poor living conditions and overcrowding presenting many challenges for the city. Over subsequent years, many positive changes did happen. Such areas have steadily become of interest for many people wanting to spend time within old Beijing. Tourism, including growing numbers of day visits, saw areas such as Nanluoguxiang, Zhonggulou and Shichahai becoming premier destinations, particularly at weekends and public holidays. However, there are still quiet areas, off the tourist path, which continue to retain a traditional feel of the hutongs.

One area, which represents a model example of successful transformation, surely is Sanlihe, a short distance south of Qianmen. For many years it remained little visited, until a project, partly finished in 2019, saw rejuvenation particularly along its restored river. Trees and gardens including traditional-styled pavilions, create a sense of tranquil beauty. Alleys have been resurfaced, domestic dwellings looking more pristine are now within a much improved local environment. Traffic-free, it is pleasurable for walking or cycling. Within the area, some local communities remain, maintaining a traditional feel of everyday alley life. It is certainly one of my favorite districts of older Beijing.

Beijing has changed considerably since my arrival in 1987, however, it is positive to observe and indeed record such ongoing work in preserving vital elements of the city's intrinsic heritage.

Bruce Connolly is a photographer and writer from Scotland who has lived in China for over 30 years. The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

If you have a specific expertise, or would like to share your thought about our stories, then send us your writings at opinion@chinadaily.com.cn, and comment@chinadaily.com.cn.